“I am a prophet also as thou art; and

an angel spake unto me”—

“A master pianist may hit a wrong note,

but everyone still knows him to be a good pianist.” —Fulton J. Sheen

[2col1]THE STORY of the young prophet of Judah often elicits a disturbing response from readers. Most of us would say that the wrong person died, that a story cannot end as this one does. Indeed, even biblical commentaries seem unsettled on how to explain what happened and why. Critics can trace the basic plot easily enough, but the narrative has implications that almost defy understanding.

My explanation may not fare any better than what others have offered. Indeed, my remarks may likewise prove rather inadequate. Even so, whether or not what I write here enhances the understanding of this narrative, I leave to the better judgment of readers and to God. However, if we look more closely at the structure of the narrative, on how the story is told, we may be better able to trace what happened and what God would have us do.

The narrative begins with a man having been sent by God to decry the dedication of an altar erected by a king named Jeroboam. Curiously, the character depicted as a man of God, is never named in the story. He is identified as a prophet by an older man who subsequently misleads him—

I am a prophet also as thou art; and an angel spake unto me by the word of the Lord —1 Kings 13:18.

Indeed, none of the characters in the story are ever mentioned by name, except Jeroboam. The impression might be that story is more parable than historical record, but the specific mention of both the king and the setting in which the story transpires precludes us from reading the story as fiction, as metaphor. This is an event that actually happened, and that, in turns, makes the tragic ending of the story even more disturbing. There are no names because any of us, perhaps, could find ourselves in a similar circumstance.

The setting proper takes place in Bethel, a city near the border of Israel and Judah. The man of God comes from Judah, but his hometown is never identified. We do not know how far he had to travel to reach Bethel. We know nothing about his family, whether he is married, or not, whether he has children. We know nothing about his age, his occupation, his personal life. We do know that he is younger than the older prophet

Interestingly enough, the story begins with the man of God from Judah publicly speaking out against the dedication of an altar. Jeroboam had erected two shrines, one in the north at Dan, and one in the south at Bethel. The intent was not to further the worship of God, but rather to compete with Jerusalem as a religious center. Because of unmitigated stubbornness and poor judgment by Rehoboam (the heir to Solomon) the kingdom had severed into northern and southern sectors. God had assigned the northern sector to Jeroboam, but repeatedly the kings from the southern sector will attempt to unite the divided kingdom by military force.

[endcol] [2col2]The clashes on the battlefield, of course, could never succeed regardless of which sector launched a military campaign. God had already intervened: For the cause was from the Lord, that he might perform his saying, which the Lord spake by Ahijah the Shilonite unto Jeroboam (1 Kings 12:15). What God has put asunder, no man can bring back together. And yet, perhaps, because Jeroboam understood the instability of popular opinion, he initiated policies intended to preserve his political status. As often in the case of government, the welfare of the people was secondary, Jeroboam’s interest was not religious as much as it was self-interest.

Whereupon the king took counsel, and made two calves of gold, and said unto them, It is too much for you to go up to Jerusalem: behold thy gods, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt. And he set the one in Bethel, and the other put he in Dan. —I Kings 12:28, 29

The name, Jeroboam, literally means, one who pleads the people’s cause, but the cause Jeroboam promoted was his own. His legacy is repeatedly described as negative, as one who taught the people to sin. The ultimate collapse of the northern sector would come at the hands of the Assyrian military, not by a campaign from Judah. Even though, the destruction of the northern sector would happen much, much later than the reign of Jeroboam, the influence Jeroboam began is attributed by Scripture as the root cause for the national collapse:

Jeroboam drave Israel from following the Lord, and made them sin a great sin. For the children of Israel walked in all the sins of Jeroboam which he did; they departed not from them; Until the Lord removed Israel out of his sight, as he had said by all his servants the prophets. So was Israel carried away out of their own land to Assyria unto this day. —2 Kings 17:21-23

The altar, then, at Bethel was crucial in cementing the newly formed government. The irony here, of course, was that the altar would ultimately destroy both government and the people it had intended to preserve. The altar did cause the people to coalesce, but only in a bad sense.

[endcol] [clearcol]

The Literary Structure of the Narrative

[2col1]The structure of the narrative is that both the opening and closing segments describe the religious policies mandated by Jeroboam. What is immediately striking, however, is that in both segments, the outcome fell far short of what Jeroboam had hoped.

In the opening segment, the dedication ceremony is abruptly interrupted by an outcry from the man of God: O altar, altar, thus saith the Lord (13:2). The apostrophic reference to the altar would have made it appear to the audience that the altar itself was an entity capable of influence and status. This particular rhetorical figure is used in elevated diction, and most likely was used here to counter any sense of awe that the dedication ceremony had sought to bestow on the moment.

The dedication of the altar may have reflected a momentous political undertaking, but not quite in the way Jeroboam and his minions would have ever imagined. The man of God continued his censure; the altar would ultimately be destroyed by a figure named Josiah, and bones of dead men would be burnt on the altar. Some 250 years later, the desecration of the altar took place just as the man of God had predicted. The king was the godly Josiah.

The auspicious policy forged by Jeroboam was not to be so easily dismissed by an outburst from someone in the audience. After all, the king himself was presiding over the ceremony. The king, therefore, ordered that the man of God be seized, but before the command could be enacted, the king’s own arm and hand froze in place. The man who just moments ago had exercised absolute power, could now not even lift a finger. Seemingly, the hand was completed paralyzed with the king having to beg the very man he had sought to imprison just moments before. The hand was restored, and a subsequent offer by the king to the man of God was publicly rebuffed.

And the king said unto the man of God, Come home with me, and refresh thyself, and I will give thee a reward. And the man of God said unto the king, If thou wilt give me half thine house, I will not go in with thee, neither will I eat bread nor drink water in this place: For so was it charged me by the word of the Lord, saying, Eat no bread, nor drink water, nor turn again by the same way that thou camest —1 Kings 13:8, 9

As for the altar, the pronouncement by the man of God had caused the altar to split in two. Ashes spilled out of its base. What may have seemed like a solemn occasion had now been turned into outbursts of royal anger, of paralysis, and of ashes. If the altar had been the symbol of daring change and hope, the scene now mirrored an unclean and tragic undertaking.

[endcol] [2col2]The imagery of ashes, of course, suggests complete devastation as when an enemy has reduced a conquered city to ashes. Ashes, of course, can symbolize repentance since the underlying notion is one of deep sorrow. In Esther we read, There was great mourning among the Jews, and fasting, and weeping, and wailing; and many lay in sackcloth and ashes (4:3). The altar of Jeroboam would become the source of unimaginable national sorrow. The man of God had addressed the altar rather than the king directly probably because the evil Jeroboam had initiated would out-live Jeroboam.

Clearly, Jeroboam had promoted the dedication ceremony in order to further his sense of self-importance and prestige. Instead of political honor, however, his paralyzed hand suggested a man and a policy less than whole, a deformed undertaking, a crippled future. Those who were present that day could not have misunderstood the ironic twist. The king who cried out, ‘Seize him,’ found himself seized.

The honor Jeroboam offered the man of God, likewise, reflected how far the king had gone into evil. The words, entreat thy God, denote an unmistakable distance between Jeroboam and God. The crass offer for official recognition and possible reward reflects how Jeroboam understood the world, and how little Jeroboam understood someone like the man of God from Judah. Since whatever Jeroboam did, he did out of a personal advantage, he thought the personal values of the man of God would have been the same. He could not fathom someone not wanting to be a part of a government sponsored hospitality and a subsequent reward from a king. Had the man of God allowed himself to accept either the invitation, or the reward, his credibility would have been compromised. People would have seen him as an ally of Jeroboam rather than as someone repulsed by what Jeroboam represented. When evil is as open and as blatant as the sin of Jeroboam, there can be no compromise. The only remedy is amputation; If that right hand offend thee, cut it off (Matthew 5:30). Such was the situation here; there had to be a clean break, an absolute distinction drawn between Jeroboam and his altar, and the man of God and his mission. Once the man of God had spoken the word of the Lord, he was to separate himself from Bethel and its environs. His speech had to be direct, his departure direct as well. To have done anything else would have been interpreted as an endorsement of Jeroboam and the altar he had built.

Perhaps, Jeroboam may have thought that by acting in the role of priest at the altar, he would somehow replicate the status of the priest-king Melchizedek. Whether or not portraying himself as Melchizedek was Jeroboam’s immediate goal, we cannot say. What is especially telling, however, is how the narrative closes. If at the beginning of the story we have a king who seeks to act the part of priest at an altar, at the end of the story, we have a priesthood, served only by the most vile in the nation.

After this thing Jeroboam returned not from his evil way, but made again of the lowest of the people priests of the high places: whosoever would, he consecrated him, and he became one of the priests of the high places. And this thing became sin unto the house of Jeroboam, even to cut it off, and to destroy it from off the face of the earth. —1 Kings 13:33, 34

Any sense of honor Jeroboam may have sought, any legacy he may have envisioned would be denied him. Jeroboam would be remembered as the king who was publicly humiliated, as the king who caused others to sin. The reference to Jeroboam and the altar he commissioned closes the narrative, and thereby comes full circle. In literature such a structure is call a ring composition with the ending segment functioning as a coda or closure.

[endcol] [clearcol]

A Private Encounter between Two Men of God

[2col1]Encapsulated within the Bethel narrative is another narrative, a counter story, a private encounter between two men of God. At first, such a story of a private interaction between the man of God from Judah and an unnamed older prophet from Bethel might seem completely harmless, almost inane. Indeed, this central story with its warm hospitality and friendship is something that any of us can easily understand and appreciate. Perhaps, such is why the tragic ending leaves us so disturbed and bewildered. The words, he lied, clearly implicate the older prophet, and yet, the immediate judgment of God falls upon the man of God who believed that lie.

As we read the narratives in their entirety, however, we discover a common bond in which the Bethel altar forms a backdrop for the tragic death of the man of God. Clearly, his death foreshadows an even greater harm to come. As he had been misled to his own death, so others would be misled to their own hurt and captivity. Jeroboam had put into motion what neither he nor anyone else could control or understand. The die had been cast. The death of the man of God would be followed by many, many deaths to come. Even Jeroboam’s own passing would not end the evil he had unleashed on generations yet unborn: “O altar, altar.”

While we can grasp the notion of literary foreshadowing, we cannot fully grasp why someone called a man of God would be condemned by God while still being referenced as a man of God. Neither can we understand why a prophet of God would have lied as he did. The old prophet was not under any duress or threat. There was no sense of personal gain. Seemingly, he simply wanted to be with the man who had risked his life to confront Jeroboam. His sons had attended the dedication ceremony, and maybe he merely wanted to hear more about what had happened. There is so much in this story that we understand and so much that we do not.

Before delving deeper into the story and its internal conflicts, perhaps we might garner better insight if we identify some of the key terms used by the writer. These would be those words either repeatedly used, or marked somehow by contextual intensity. Either way, we are looking for words that extend beyond the literary horizon, words that leap out to draw our focus. When we analyze the narrative in this manner, one facet that immediately stands out is that Jeroboam is mentioned by name only four times in the chapter. From a cursory perspective, this surprises us since clearly Jeroboam is a central figure in the story. He is the only figure mentioned by name. However, the king is not the focus. In fact, a donkey is mentioned more times than the name of the king.

In contrast to the paucity of references to the name of Jeroboam, the unnamed man of God emerges as the core figure, as the protagonist with the phrase, man of God, being mentioned some fifteen times

The Altar Dedication (1-10)

“There came a man of God out of Judah” (1)

“Jeroboam heard . . . the man of God” (4)

“According to the sign which the man of God had given”(5)

“The king answered . . . the man of God” (6)

“And the man of God besought the LORD” (6)

“The king said unto the man of God” (7)

“The man of God said unto the king” (8)

At the Prophet’s Home (11-32)

“His sons . . . told him all . . . the man of God had done” (11)

“His sons had seen what way the man of God went” (12)

“And went after the man of God” (14)

“He said unto him, Art thou the man of God?” (14)

“And he cried unto the man of God” (21)

“When the prophet . . . heard thereof, he said, It is the man of God” (26)

“And the prophet took up the carcase of the man of God” (29)

“When I am dead, bury me in the sepulchure wherein the man of God is buried” (31)

Coda (33-34)

No references to the man of God

[endcol] [2col2]The phrase, man of God, occurs in both major narratives relatively the same number of times. The coda, of course, does not use the phrase, but rather underscores the lasting and evil influence of Jeroboam. Such might lead us to conclude that, unlike Jeroboam, the influence of the man of God was short-lived, his denunciation of the altar probably seen more as actor speaking his lines on a stage. Perhaps, some people did listen to him. We would like to think that. Seemingly, though, for the most part, his words were soon forgotten— Strait is the gate; and narrow, the way, and few there be that find it (Matthew 7;14). From our limited perspective in life, evil seems to have greater sway and influence.

Clearly, his description as a man of God implies an abiding inner quality, a depth of character as someone who lives for God. What is especially striking about this story, however, is that antagonist, or principle opponent, is not Jeroboam but rather a prophet similar to the man of God. At least, that is how the old prophet describes himself: I am a prophet also as thou art (13:18). Later in the narrative, the man of God is again referenced as a prophet, but the syntax is very awkward. In fact, the narrator must go out of his way to explain that he means the man of God when he says prophet. There is a sense of incongruence in the words— He saddled for him the ass, to wit, for the prophet whom he had brought back (13:23).

There is a chilling effect to the sentence as well. The man of God is referenced as prophet as he leaves the home of his host. The irony is quite crushing. The man of God leaves the premises knowing that he has not done as God had said. He also is keenly aware that in death he will not be buried at home. If the initial reception and welcome had been marked by friendliness, warmth, and joy, the departure would have been marked by regret, sorrow, and despair both on the part of the old prophet and the man of God. Each had disobeyed God. The one had lied; the other had failed to heed a divine edict. What is especially disturbing, however, is that the old prophet, whose exuberance had brought about the tragedy in the first place, is the one whom God compels to speak the sentence of doom. We can only imagine what each man must have felt at that moment. Perhaps, just moments before they had shared a toast, or had commented on the food, or the occasion for the meal. Most likely, they had talked about God and the disgrace of Jeroboam. The conversation, like the meal, came to an abrupt end.

It is important to note that after the death of the younger man, he is again called the man of God. Seemingly, he did not cease to be a man of God because he had made a mistake. It would seem that we are to understand that what he had done was out of character for him.

And when he was gone, a lion met him by the way, and slew him: and his carcase was cast in the way, and the ass stood by it, the lion also stood by the carcase. And, behold, men passed by, and saw the carcase cast in the way, and the lion standing by the carcase: and they came and told it in the city where the old prophet dwelt. —1 Kings 13:24, 25

[endcol] [clearcol]

How Bad Can Good People Be?

[2col1]This short narrative within the larger Jeroboam story elicits a sense of shock and even disbelief. The event, however confusing, certainly causes us to think about ourselves. Both men, of course, had disobeyed God, the one failing to carry out what God had explicitly said, and the other, simply had lied. Neither had done so out of malice or some other sinister motive. Indeed, probably each simply had welcomed the chance to visit with the other, given that both men were followers of God in a godless time.

It certainly is easy enough to say that the man of God should have carefully followed what God had said regardless of what anyone may have said to him. After all, let God be true and every man a liar (Romans 3:4). And yet, it is inescapable that he was misled by another man of God, lied to by a prophet of God. We might argue that the older prophet of God was not a true prophet, that he was fraudulent; however, the text does not seem to bear that out.

What is disturbing is that a prophet of God could lie to another man of God and be the cause of his death. It would seem to us that the one who had lied should be the one more severely punished, but that is not what happened. What we can say is that each of us must listen to God above all else, and never allow ourselves to do or believe something God had not said, or has forbidden. Further, we should not lie, even in a seemingly harmless matter. That much is true.

And yet, what is beyond the clearly evident is the question of how good people can do bad things, and further, how someone who has done something bad can still be called a man of God. Admittedly, all of us fail to live as God wants—

If we say that we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us. If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just to forgive us our sins, and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness. —1 John 1:8, 9

Given that human frailty is what it is, we can say that a good man who does bad does something out of character. Likewise, the evil man who does something good does something out of character. There is a central core to each of us—

The good sometimes do wrong. Let us face it. And when they do wrong it is the same as the evil who do wrong. Evil is an exception in the life of the good; it cuts across the road of their life as a tangent. With the evil, good is an exception. A master pianist may hit a wrong note, but everyone still knows him to be a good pianist. A beginner may hit a right note, but everyone know that he is not a good player (Sheen, Way to Inner Peace, 87).

Someone may argue, however, that life is more than hitting the wrong note in a concert. Certainly, evil is more than a mistake, and yet the Lord confronted evil while still seeing the good within a person. The woman at the well, for instance, is told she had done wrong, but the Lord saw more than the wrong in her. She had had five troubled marriages, and now was even living with a man outside of marriage —

Thou hast had five husbands; and he whom thou now hast is not thy husband: in that saidst thou truly. —John 4:18

Her life was in an upheaval, yet she was the kind of person for whom Christ came.

In one sense, the whole notion of how good and bad interact within us is something we cannot fully understand. We do know, however, that good people can do bad things, and still be good. Even when the wrong is irreversible, as in the case of David’s affair with Bathsheba, somehow the good within David remained. He repented, but the evil he had done could not be undone in this life. Yet, at his core, David was still David.

In this particular narrative, the unnamed old prophet lied, and even though his lie was not uttered out of malice or intent to harm the man of God, the fact remains that he misled a good man, resulting in his ultimate death. The unnamed man of God, however, also did wrong, and his wrong may have even been a greater wrong. The man of God had dismissed the word of God.

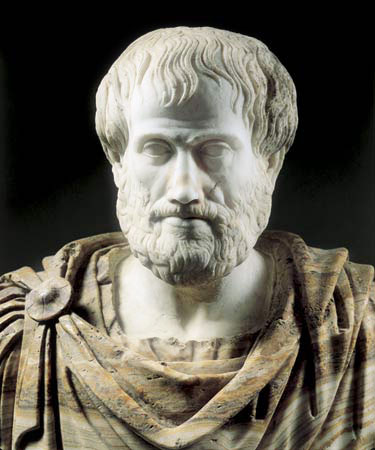

[endcol] [2col2]In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle argues that a good man can indeed act out of character. A just man can even commit a serious injustice, such as adultery, or theft and still at the core be a just man. Aristotle argues that is a matter of proportion:

But since it is possible for a man to do an act of injustice without yet being unjust, what acts of injustice are there, such that the doing of them stamps a man at once as unjust in this or that particular way, e.g. as a thief, or an adulterer, or a robber?

Perhaps we ought to reply that there is no such difference in the acts. A man might commit adultery, knowing what he was about, and yet be acting not from a deliberate purpose at all, but from momentary passion. In such a case, then, a man acts unjustly, but is not unjust; e.g. is not a thief though he commits a theft, and is not an adulterer though he commits adultery, and so on. —Book V (1134a20)

Aristotle is not saying that we can do wrong and somehow not be blamed for that wrong. Rather he is drawing a distinction between the absolute and the proportional. Earlier in the same chapter, Aristotle explains justice as a proportion:

Justice is a sort of proportion . . . an equality of ratios . . . what is proportional and what is unjust violates the proportion. —Book V (1131a30; 1131b15)

Aristotle is concerned about restoring what has gone wrong with requital being proportional to the act itself. When we think about a man’s life then, it is the proportion that makes us say that a good man is really a bad man rather than saying a good man had done something bad. People can and do act out of character. Aristotle understands injustice as an imbalance with requital attempting to restore the balance that has gone awry. Yet, at times, the balance simply cannot be fully restored.

The whole notion of proportion and of the inner soul is something that ultimately belongs to God. That is why judging others or even ourselves causes us to go askew. We simply cannot see the heart, not even see our own. We certainly cannot see the entire life of a man, including motives, and hidden thoughts. Yet, it would be wrong to say that we should never judge, never say that someone has done wrong. Clearly when a good man has committed adultery, he has committed adultery. We cannot and should not say otherwise. Yet, when his life is viewed as a whole, the conclusion can be very different than the wrong he has done. Certainly, we know evil when we see it, but we need to see good as well and not render judgment that belongs to God:

Who art thou that judgest another man’s servant? to his own master he standeth or falleth —Romans 14:4.

In this life we only see a part of anything, of even ourselves.

[endcol] [clearcol]

Tabur Ha’aretz, Elon Moreh Settlment, Photo courtesy of Biblewalks.com

Excerpts from Nicomachean Ethics are from the translations by J. A. K. Thomson, 1953 (V.1131a30, 1131b15); and F. H. Peters, 1893 (V.1134a20). Two articles of note from a philosophical / classicist perspective are Howard J. Curzer, “How Good People Do Bad Things: Aristotle on the Misdeeds of the Virtuous” Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy, vol. 28, no. 1, 2005, pp.233-256. and Nancy E. Schauber, “How Bad Can Good People Be?’ Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, vol. 17, no. 4, 2014, pp. 731-745.

Fulton J. Sheen, Way to Inner Peace, 1955 is something I ran across by chance, largely, I suppose, because of my father’s influence.