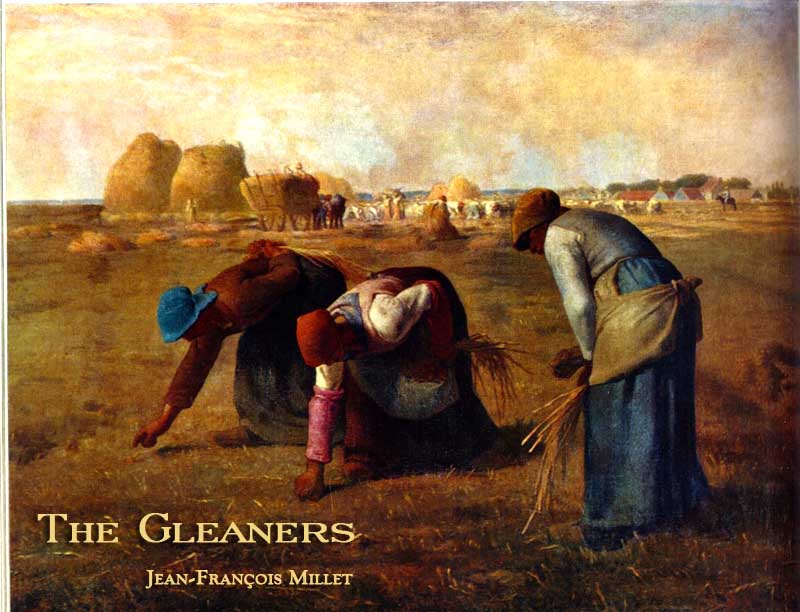

Les Glaneuses, a painting by Jean-François Millet

Gleaners we are, all of us —

“The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.

From the desperate city you go into the desperate country. . . .” —Thoreau

![]()

The sun is shinning brightly, but not on the gleaners. In the background are hired workers, people fortunate enough to have jobs, and healthy enough to work those jobs. These are bathed in sunlight; their clothes are pure white. Not far from the hired workers stand two abundant stacks of grain, symbolizing a crop of overflowing prosperity. A wagon with oxen stands nearby while in the distance a man sits astride a horse. The man is a steward perhaps, or maybe the owner of the field. Because he rides a horse, he sits above the work and as a result, is much more removed from the earth than either the hired workers or the gleaners.

We cannot be sure of the intended significance of some of the images, but we can be sure that the hired workers are not alone. These work as a group, having resources such as oxen and wagon readily available. The tall stacks of grain suggest a coming end to their labor. And because they work as a group, the hired workers share the oppressive toil, thereby diminishing some of the harshness of the task.

Since the three gleaners parallel one another, the suggestion might be that of a common bond, of a sameness of life. The posture of the standing gleaner might suggest a small difference, but the reality of it all is that all three are equally and forever tied to the earth. The life they live now will be the life they live tomorrow and the life they will live until there is no more life on this earth. In life they lived on the bronze earth and in death, their bronze corpse will return to the bronze earth.

There is another artistic element, which we should not overlook in the painting. Millet has reversed light and dark tones by placing the light color in the background, and the heavier color in the foreground. This juxtaposition of a light background against a dark foreground further adds a sense of dissonance to the mood of the painting. What should be seen as near is actually far away and what should be seen as distant is immediately before us. It is almost as if the poverty of the gleaners is a life from which there is no escape. We may see the brightness, but it is always distant and removed, beyond our reach but not beyond our sight.

| From dust God formed man |

God later cursed the serpent, “Upon thy belly shalt thou go, and dust shalt thou eat all the days of thy life” (Gen. 3:14). Because the serpent had tempted Eve with fruit that hung on branches of a tree, and therefore, far above the dust of the ground, the serpent would now be confined to the dust of the ground and from that dust the serpent would eat.

As for man, dust also played a part of the curse as well: “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground; for out of it wast thou taken: for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return” (Gen. 3:18). Man would return to the dust from which he had been formed, and until his life was over, he would work against the dust of the ground for his bread, for his life, for his whole sustenance. His life and his death would be inseparable from the dust, which at once, depicts both his origin and his destiny. Since man was made from the dust, we might expect there to be some affinity between man and the substance from which he was made. To be sure, there is affinity; however, just as enmity will exist between the woman’s seed and the serpent, enmity will exist between the man and the dust from which he was made and will return. What should have been alliance, given that man was made from the earth, now will become sweat, disappointment, and a life of hard labor.

Yet, we are inexplicably fascinated by the earth– perhaps as much as we are dependent on the earth. A man may look up at the stars and dream, but he must look down at the plate from which he eats. Not all of us can be farmers, but it is the farmer among us who has the realistic view of life. He hands are in the soil, his feet are on the ground, and he sees straight. Otherwise, he ploughs the field in crooked and unsightly furrows.

The lawyer thinks about law, but you cannot eat law. The engineer thinks about math, but you cannot eat math. The businessman thinks about money, but in the last analysis, you cannot eat paper money. The fact is that because we are made from the earth, we are intertwined with the earth. We build our homes on the earth; we get our food from the earth, and when this life is over, we return to the same earth from which we were made.

Like Solomon, we may build houses, plant gardens, plant orchards and vineyards, and even make for ourselves pools of water to refresh ourselves on a hot afternoon. We move the earth to make highways, and talk about the majesty of the earth as a mountain or the wonder of the earth as a canyon. We may hike through the quiet of a forest planted in earth, but in the last analysis, whatever the landscape, and whatever we do, God has determined that our life be intertwined with the earth from which we came:

There is nothing better for a man, than that he should eat and drink, and that he should make his soul enjoy good in his labour. This also I saw, that it was from the hand of God. —Ecclesiastes 2:24

I think that I shall never see,

A poem lovely as a tree;

A tree whose hungry mouth is prest,

Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in Summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Poems were made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.

Even in sacred literature, the sentiments are much the same. Something within us identifies with the earth. We find solace in the earth images of Psalm 23:

The LORD is my shepherd; I shall not want.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures,

He leadeth me beside the still waters,

He restoreth my soul.

We find comfort in images of still waters and green pastures. Instinctively, we somehow recognize the images of Eden and the life we once lived. Nothing else can restore our soul as well as the beauty of a garden of earthly delight.

We stand beneath the branches of the giant Sequoia and look up in awe all the while rooted to the same earth as is the tree. We are of this earth.We marvel at the spring growth of a tree we planted the year before and become ecstatic when we taste fruit from its branches. In our older years, we till the soil of a garden, planting food which we could just as easily buy at a store, but plant we must. With our hands in the dirt, we have the same thrill of a child at play in the dirt. From the earth we are made.

During the special moments in life, we send flowers to friends, flowers which once grew in the earth, but once plucked from the ground soon wither. We may not be planted in the soil, but we are as dependent on the soil as is the flower.

Connected to the earth we are, and to the earth we return, but our spirit returns unto God who gave it.

| Ruth gleaned in a field |

Whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God. — Ruth 1:16

When the two women finally reach Judea, Ruth goes into the fields to glean, without knowing that God had prepared for her a new life, a new beginning. She would become the wife of a wealthy nobleman named Boaz and she would become the mother of a child with a future beyond anything she could have ever dreamt.

Boaz took Ruth, and she was his wife: and . . . she bare a son. And Naomi took the child, and laid it in her bosom, and became nurse unto it.

And the women, her neighbours, gave it a name, saying, There is a son born to Naomi; and they called his name Obed: he is the father of Jesse, the father of David. —4:15, 16, 17

Certainly, no one in that small village would have ever suspected that the child born to Boaz and Ruth would become the grandfather of David and an ancestor of the Christ himself. Others in the village may have rejoiced with Namoi at the birth of Obed, but no one except God knew just how far the blessing of that child would reach. The villagers could only see the young child and the joy on Namoi’s face, but only God could see the painting and the distant future.

Like Ruth, we may become gleaners in the field of life. Our monies may vanish; our homes taken from us, our jobs given to another. We may literally find ourselves in a soup line, doubting ourselves and what we have lived for. We may claw with our bare hands at the soil in futile hope. When the heaviness of life becomes inconsolable, and our grief becomes more than we can bear, when are reduced to gleaning for our daily scraps of food, we need to remember Ruth and the God who is near. We need to lift up our eyes.

—James Sanders

Behold, I say unto you, Lift up your eyes, and look on the fields;

for they are white already to harvest.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.